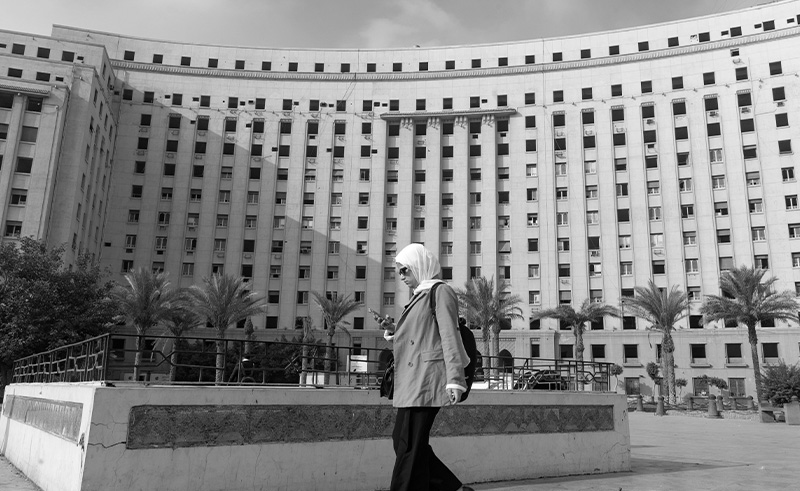

Economic Exclusion & the Reality of Women’s Labour Rights in Egypt

While women-led businesses account for 23% of entrepreneurial activity in Egypt, true economic empowerment remains a challenge.

For Egypt, the journey toward true and tangible empowerment of women’s rights remains layered with complexities. Despite various government initiatives and constant public discourse surrounding feminist issues, the core problems persist, deeply rooted in the systemic socioeconomic and cultural exclusion from public spaces faced by Egyptian women. Economic exclusion does not just mean missed job opportunities; it reinforces the cycles of social subjugation that have been rampant in Egyptian society for decades past. When women are denied active roles in the economy, they are, by extension, distanced from decision-making processes within society itself, and relegated to the “traditional” domestic roles within the household. Empowerment efforts as they stand don’t address the foundational issues that perpetuate economic barriers for Egypt’s women, especially those who are underprivileged. Real progress will require a broader approach that goes beyond the office walls and into the structural frameworks limiting women's potential.

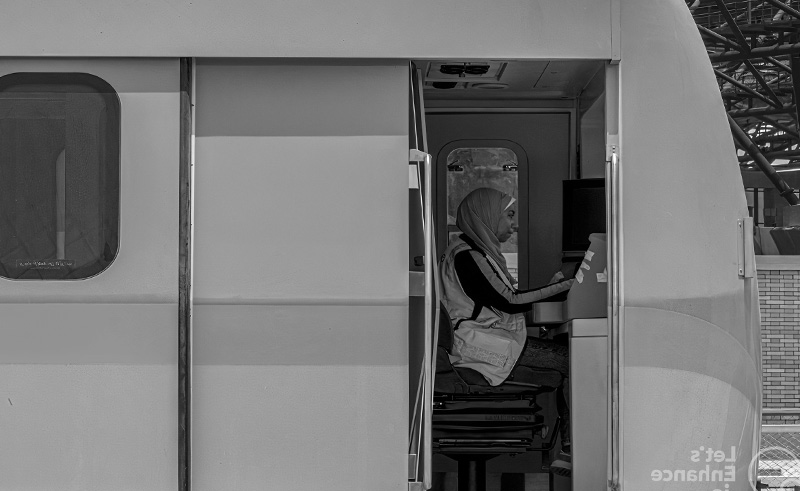

‘Career summits’ centred around empowering women in the workplace, emphasising support systems for career advancement, mentorship, and leadership development have become reputable spaces for fostering gender equality and building professional networks for women. They are valuable platforms for empowering women in the workplace through mentorship and career advancement workshops. In Egypt, these efforts align with broader trends in promoting female entrepreneurship, which has shown notable progress in recent years. Female entrepreneurship in Egypt represents a significant avenue for economic inclusion and empowerment, with women-led businesses accounting for approximately 23% of all entrepreneurial activity in the country, per a UN Women report published in 2022. Entrepreneurship has been a major area of focus as part of Egypt’s 2030 vision, with women led-businesses spanning diverse sectors, including technology, fashion, and food services. Additionally, there has been a marked increase in women participating in tech-driven businesses, a reflection of enhanced digital skills training and investments in the startup ecosystem.

However, while focusing on these areas is undeniably important, it still reflects only one dimension of women’s empowerment. Looking at their workshop offerings, it becomes evident that these efforts, while progressive, are most applicable to women who have already overcome the initial hurdle of entering the workforce, which a significant portion do not. Labour participation rates for women in Egypt have consistently declined over the past decade, from 24% in 2012, down to a mere 17% as of 2022, according to the World Bank, one of the lowest rates in the world. This shows that the majority of Egyptian women remain excluded from formal economic activities, highlighting the disconnect between inclusion initiatives and the realities of systemic exclusion that still exist. These summits highlight a broader need to expand our understanding of empowerment beyond workforce ‘engagement’, and address the real factors affecting women’s economic agency on a much deeper level.

For many women, economic participation is not just a personal ambition but an uphill battle against a myriad of social and structural challenges. Economic and social barriers are significant, especially for women in rural and lower-income communities, where job opportunities are sparse for everyone, wages are lower, access to financial tools remains limited, and social expectations consistently exclude women from accessing resources outside the home. Working women in these areas often face not only a lack of resources but also immense pressure to act as both the breadwinner, and dutiful caretaker. A 2020 survey by the Egyptian Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) found that approximately 18% of Egyptian households rely primarily on women to bring in an income, a trend which rings especially true in more underprivileged areas. It's also important to note that this statistic excludes women who work in the ‘grey’ or informal economy, otherwise the figure would be significantly higher. However, cultural norms continue to place a high premium on women’s roles as homemakers, framing professional pursuits as secondary or even contradictory to women’s expected responsibilities.

In the more rural parts of Egypt, where traditional views are deeply entrenched, stepping out of the home to work can be seen as culturally inappropriate, if not outright taboo, and these factors are compounded by a lack of access to quality education and pervasive sexual harassment, make pursuing job opportunities very costly. So, while urban women might have some pathways for personal and professional development, rural women are often left behind, with limited access to schooling and programs that would otherwise enable them to build sustainable careers.

In response to these challenges, the Egyptian government has rolled out several programs aimed at empowering women economically. Initiatives like the ‘Decent Life’ project (Hayah Karima), launched to improve living standards in rural areas, have brought attention to women’s roles within economic development. Programs supporting female entrepreneurship, microfinance loans, and vocational training have attempted to give women the tools to achieve financial independence.

However, these initiatives have produced mixed results. While they have succeeded in raising awareness and creating some opportunities, many of these programs predominantly benefit urban, middle- to upper-class women. In particular, government efforts fall short when it comes to reaching Egypt's marginalised women. Without tailored outreach, the programs risk perpetuating further inequality within the very demographic they aim to empower. For example, microloans are not truly accessible to women who lack basic financial literacy or collateral, leaving rural women still excluded from economic participation, or worse, lead to further exploitation in cases where there’s a lack of proper understanding of debt instruments.

Programs that do make it into rural areas sometimes struggle with implementation due to logistical issues, lack of proper resources, or insufficient attention to specific local community needs. The focus on entrepreneurship, while beneficial for some, is not a viable solution for many rural women who lack both the capital and the market access required to sustain a private business. Such structural gaps reveal that although these initiative’s intentions may be well-placed, their execution and implementation require far more refinement to make any real impact.

Factors like disparities in access to basic resources and inadequate social protections continue to impede the full participation of Egypt's women in the economy. Many women lack the necessary documentation to access government services, further excluding them from economic opportunities. Legal protections also remain insufficient. While laws addressing workplace harassment and discrimination exist on paper, their enforcement is inconsistent at best, particularly outside urban centres, leading to more barriers to emancipation. Additionally, social safety nets that could support women through financial crises, health issues, or family obligations are virtually non-existent for rural women. Without reliable support, these women continue to face significant risks in even attempting to pursue work outside of the home.

To achieve meaningful change, Egypt’s approach to women’s empowerment must go beyond workforce initiatives and focus on dismantling the structural economic and social barriers that limit access to opportunities. A key priority is expanding social programs designed to address the unique needs of rural and lower-income women. Establishing community-based training centres that provide market-relevant skills, and financial literacy can empower women within their local environments. Evidence-based policies are crucial, as studies from comparable nations demonstrate that cash-transfer programs linked to education or skill development significantly enhance women’s participation in the labour market. Equally critical is the consistent enforcement of existing workplace protections.