The Rise & Fall of Airlift Technologies - An Insider Analysis

Less than a year since its record-breaking $85 million dollar raise, the delivery service is shutting down. EquiTie founder Ahmed El Hamawy shares his insights on the implications of this crash...

Lauded as the poster child of the Pakistani ecosystem and a harbinger of a brand new era for startups in emerging markets, it seems the air has been knocked out of Airlift Technologies. Less than a year since its record-breaking $85 million dollar raise, the instant-delivery service provider has announced that it’s shutting down. The news may have sent shock-waves through the ecosphere and with it a bleak prognosis for ‘emerging markets’ but according to Ahmed El Hamawy, the warning signs weren’t just there, they were glaring.

Ahmed El Hamawy is the CEO of EquiTie, a leading investments and advisory firm with keen insight into the Pakistani startup ecosystem, most notably through its involvement with Dastgyr, one of its portfolio companies. Launched in 2020 with a focus on Pakistan’s underserved B2B e-commerce market, Dastgyr is in fact the brainchild of two Airlift founding team members who wanted to pivot away from Airlift’s quick-commerce model. EquiTie was the first and largest institutional ticket in Dastgyr’s seed round and advised them through their $37M Series A, the biggest in Pakistan’s history.

All of which gives El Hamawy unique insight and perspective on the Airlift Technologies implosion and its implications. In this special edition of StartupScene’s #InsiderInsights, El Hamawy offers an analysis of the current state of the Pakistani fintech ecosystem, the opportunities that exist for new entrants, and how this translates to Egypt and other emerging markets.

This is his #InsiderInsight…

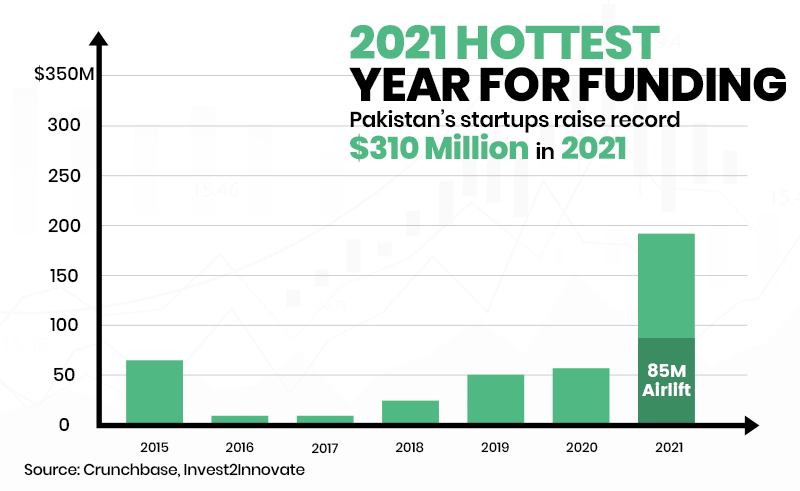

Launched in 2019, Q-commerce retailer Airlift Technologies was considered Pakistan’s top startup. An unprecedented Series A round at $12m in 2019 and Series B raise of $85m last year, saw them raise in 2021 more than the total amount of funding announced by all startups in Pakistan combined in 2020. The news naturally sparked reams of global coverage and with it hyperbolic pronouncements about the startup and the sector’s exciting future. On July 13th 2022, less than a year after their historic raise, Airlift Technologies announced it had permanently shut down operations. Once again the news sparked reams of global coverage and with it hyperbolic bleak pronouncements about the not so exciting future of ‘emerging market’ ecosystems.

Airlift’s crash, however, does not change any of the fundamentals that make Pakistan one of the most exciting emerging markets. This young, highly unbanked and underserved population is still in dire need of technology to solve the many problems faced by one of the poorest countries in the world.

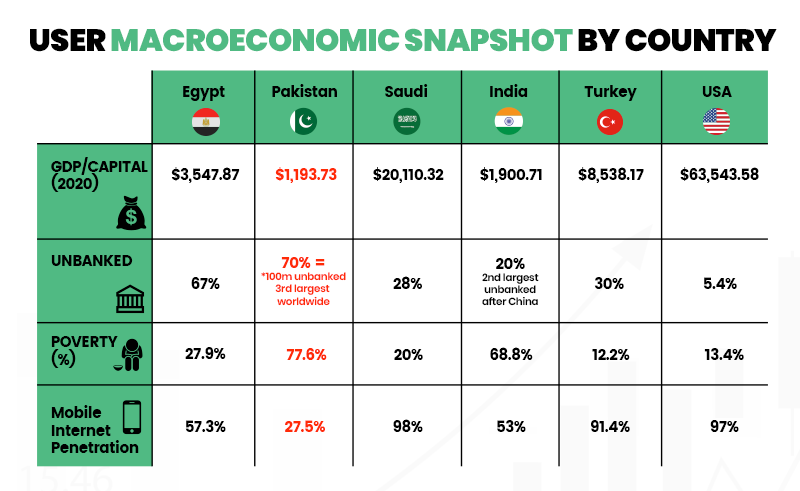

In 2021, Pakistan’s GDP per capita ranked 178th out of 216 countries, meaning the average citizen generates one of the lowest disposable incomes in the world. Despite this, many new entrants to investing in the Pakistani ecosystem often bucket it with ‘Emerging Markets’, which include more economically developed countries like Turkey and Saudi Arabia. The economy of Turkey is defined by the IMF as an emerging market economy. So it’s easy to assume since Turkey’s Getir, which is similar to Airlift, became a billion dollar company rather quickly, the same model can be applied in Pakistan. However, Turkey’s GDP per capita is 7x that of Pakistan, while Saudi Arabia’s is 17x, which means there’s much less disposable income to be paid for convenience and a much lower opportunity cost in wasting time shopping. To drive the point home, Pakistan’s GDP per capita is less than 2% of that of the United States.

As of 2020, Pakistan became the fifth most populous country in the world, with a population of more than 200 million people, and one of the fastest-growing middle classes.

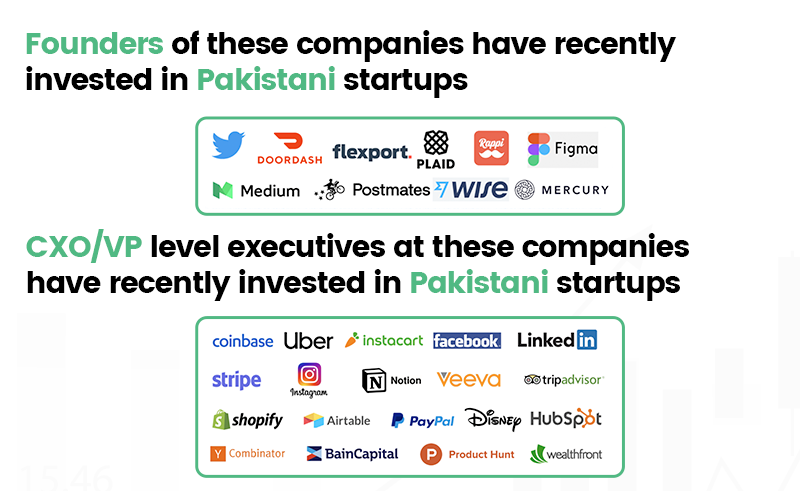

Surprisingly, while the fundamentals were there, only recently did investor interest in Pakistan boom, akin to discovering a small goldmine. In 2021, VC funding in Pakistan exceeded $310m, more than the past four years combined. The likes of Kleiner Perkins, A16z and other global investors accounted for 80% of funding.

In many ways, Airlift was considered the trailblazer for this nascent ecosystem. And a favourite to international VCs.

BEHIND THE OPTICS

The easiest thing in the world is to see anything fail and then list all the factors that went wrong, and what should have been done instead. Hindsight bias is a beautiful thing. What is more challenging and more important is to have Michael Burry’s foresight (as played by Christian Bale in ‘The Big Short’) when looking at the market in the summer of 2021.

So in an attempt to avoid hindsight bias, this analysis focuses on August 2021 and before - contextualising the brewing phase - rather than tunnel visioning on today and what went wrong in 2022.

If we take it back to August 2021, we’ll see funding records breaking across the board with financing abundant. Valuation multiples were at an all-time high and the cost of capital was the lowest we’ve seen to date.

Unfortunately the quality of capital offered and the localisation of solutions being funded were glaring warning signs that when closely examined, would show that it was all a counter-blessing in disguise. Behind the surface optics of high valuations and low capital cost, early-stage startups in Pakistan and Egypt were entering into the eye of the storm and fell victim to several macroeconomic factors that made things look very different to what they actually were.

More than 75% of Pakistanis live below the poverty line while in Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the US, this number is more than flipped with less than 25% only living in poverty. Turkey’s mobile internet penetration is 91%, Saudi Arabia’s is 98%, while Pakistan falls short at 28%. 70% of the population is unbanked, which is the 3rd biggest unbanked population in the world, while Saudi and Turkey have 70% banked, which is - again - flipped.

For the purpose of simplicity, let’s take an average user in any emerging market. When they have a dollar at hand, they have two choices: either consume or invest. And in both cases, the problems faced by this potential user are countless, whether it is the many supply-chain inefficiencies that end up being paid out of the end user’s disposable income, or the limited options to earn a return when investing. In the US or India or Turkey, these problems were solved to a large extent by using technology to empower the user directly, so they can order groceries or buy stocks through a smooth and affordable experience on their phone.

If we take solutions like Getir in Turkey or Robinhood in the US at face value and apply them to markets like Egypt or Pakistan, in my opinion, the fundraising could be a walk in the park but the failure of the startup is almost guaranteed, due to lack of product-market fit. Great products that simply don’t solve the problems in these markets. Ever thought about why Amazon and Alibaba, the two trade giants of the two largest economies in the world, have completely different products? Because they are in completely different markets.

BURN & BLIZZARDS

Early-stage startups have a straightforward yet tricky formula to crack. You get VC funding early on to “burn” cash to find product-market fit. Their product is simply a solution empowered by technology that the end user is willing to pay for, at a price higher than what it costs the startup to deliver. In other words, it’s a matter of positive unit economics.

To make things a little simpler allow me to provide another metaphor.

Imagine a group of campers in the Arctic who are trying to maintain warmth through only one fire. This fire is fuelled by logs provided at first by a wood seller. They give enough logs for free to get the fire going, but to keep it burning, the campers must pay for additional logs. For the most part, the campers eagerly engage in this deal after they experience the glories of the warmth emitted by the fire. More and more campers are likely to enjoy the night, rather than suffer through it. But if you throw in too much wood, you might reach all campers but if there’s too much wood the whole camp will burn down. And if the campers see the fire as a luxury, they might start to prioritise food and internet. They might not pay you for the wood, thus the fire might go out in the middle of the night.

If we push this further, let’s imagine the campers as the customers of a startup. The wood is the cash - the first few logs are given for free by VC funding, who sell capital or in this case, wood. The founders are the burn-managers, the warmth is the product, the fire is the startup’s lifeline, and finally, the morning is the exit.

It seems like a simple formula, but what happens when a Covid-shaped blizzard hits the camp? Without the warmth of the fire, the campers might not survive.

So what do founders or “burn-managers” need to ensure that the fire is sustained until dawn?

1. We need wood sellers who will give support as long as possible

2. We need campers that can afford warmth, within our reach

3. And finally, we need unit economics to make sense, which means for the next camper to feel warm, the price they’re willing to pay for warmth covers the cost of the additional wood, flint, scraps and whatever is needed to offer the warmth (or the solution to the problem). At the end of the night the wood-seller needs to make money

Cash flow management is how much wood needs to be thrown into the fire for the heat to last all night long without burning everything around it. So if you only need a few logs and you get a sudden shipment the size of the Titanic offloaded, as the burn-manager, your responsibility is to use only what you need. But what is unutilised creates a ‘cash-drag’ and the shipping company that brought you the wood, or the investor, will not be happy when they see their cash is not translating into growth, and instead the wood is getting wet and mouldy on the sidelines.

So that pressure forces founders, or you as a burn-manager, to keep throwing logs at opportunities and problems and allow your fire to keep getting bigger. Yes, more and more people are warm and happy, but sooner or later it gets too big and no firefighter can save the campers or stakeholders, and your whole camp from going up in flames. Speed of growth and economic sustainability are not mutually exclusive.

WHY DOES THIS MATTER?

From 2020 to 2021, Pakistani startup growth outpaced the growth of local VCs. Startups were forced to seek international VCs for capital, despite them being unfamiliar with this specific market and its users’ challenges. Rather than using first principles thinking, these VCs often look for models that worked elsewhere, believing they would work in “similar” markets. This resulted in a massive mismatch between the needs of those funding growth ‘today’ and the wants of the users that could and should turn the early-stage startup into a viable, sustainable and profitable business in the future.

This problem was magnified by the entry of Tiger Global, Softbank and other equity growth firms who were more aggressive in their investing approach, with lighter due-diligence and larger checks. This ultimately placed a greater responsibility on founders to manage upwards to truly build a customer-centric solution, while facing pressure from investors that want to see metrics growing almost at any cost.

One of the main takeaways from all this is that consumer habits are very different when we look at “similar” markets, Egypt vs. Saudi Arabia for example or Pakistan vs. India or any of them vs. Turkey or of course the US. However, very small differences can play huge roles in defining winners and losers (read learners).

If we look at Careem, arguably one of the most successful startups to come out of the region, with a model built around the localisation of Uber’s offering through cash payments, call centres, and loyalty systems that made it win market share. While these differences may look minor, they had a major impact on building the billion-dollar company. The same can be said about Fawry’s availability country-wide or Souq’s focus on electronics rather than books.

Due to the relatively low level of disposable income coupled with low banking penetration, Egypt and Pakistan would not work well for Q-commerce ‘as-is' just like commission free investing such as Robinhood’s model aren’t and shouldn’t work.

Simply put, the problems amalgamate much earlier than the moment the user or customer decides to consume or invest. Unless solved from the root, these solutions can only act as freebies from investors to users but once the economics need to be flipped, and burn needs to turn into income, reality hits hard. Especially when the solution on the cost side is a capital intensive solution that needs a lot more than software to operate. Or in this case needs the construction of buildings (capex) to sustain the fire.

The problem isn’t fast delivery or commission-free investing, nor does it live at the last mile of delivery of products from shelves, it's rather about the availability and access to these shelves in the first place. Giving the user an app to order in 30 minutes when they can pick it up from the closest convenience store (with Pakistan having more than two million) in 5 minutes isn't solving the problem, and one can argue it’s missing the point completely.

SO HOW DID ALL THIS FUNDING COME IN?

It links back to the Covid-shaped blizzard mentioned above. The uncertainty and lockdowns caused by the pandemic clouded almost everyone’s judgement because they were living in unprecedented times. It made sense to order things at home through an app because going to the store was life-threatening and extremely limited. The moment going to the store became normal, the product turned from a need (life or death) to a luxury (a 5 minute walk or a 30 minute wait).

Now users are prioritising other things like food, entertainment or clothing. They’re opting out of comfort and convenience, and focusing on essentials or other missed opportunities like travel. When the blizzard passed and the fire’s warmth was no longer essential for survival, almost every other expense became a more important necessity for the campers, and the fire could no longer burn.

A new blizzard just arrived and the campers need the warmth more than ever but this time the logs are expensive and the burn-manager that will keep the right harmony will win the Arctic. Airlift will only be the beginning of many similar fires that will follow in the next 12 months in Pakistan and Egypt.

Now that we can see a new blizzard taking over, who will stay warm enough to weather this storm?